Abstract

In this presentation, I will examine the representation of Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang in the parliaments of early twentieth-century China, particularly in the Political Consultative Council(Zizhengyuan 資政院) of the late Qing and the National Assembly of the early Republic. I identify two distinct, but intertwined, modes of representation of border regions: a patrimonial model, which maintained aristocratic privileges in exchange for loyalty, and a nation-state model, which envisaged equal status for border regions alongside Han-majority provinces. By reconstructing these two modes of parliamentary representation, this talk will place China's constitutional debates in a broader Eurasian context, showing how global trends in governance have intersected with China's efforts to assimilate its diverse border populations into a unitary nation-state.

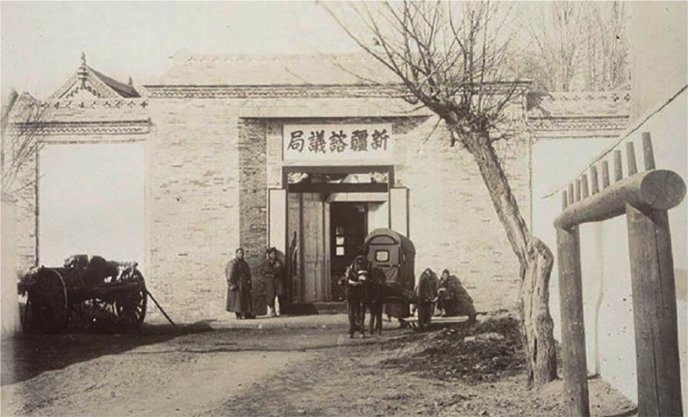

Since the formation of the Daicing (Qing) Empire in the 17th and 18th centuries, these regions had been administered under arrangements distinct from the provinces. Mongolia and Tibet remained under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Outer Regions Affairs(Lifan yuan 理藩院). Xinjiang was officially made a province in 1884, but continued to be treated in many respects as a frontier territory. When the Qing government announced its "governance reform" in the years 1900, the status of the confines played a central role in debates over the adoption of an imperial constitution. I show how parliament was conceived as an instrument of national unification rather than a means of representing imperial diversity. Moreover, Chinese intellectuals and officials, aware of the competition from emerging parliamentary institutions in Russia and the Ottoman Empire, feared that constitutional and parliamentary movements among Mongols, Tibetans and Muslims would lead to the separation of these regions if the Qing Empire did not carry out similar reforms. They therefore hoped that parliamentary representation could serve as a tool against centrifugal tendencies at the frontiers.

However, they rejected the direct application of the constitutional framework to the frontier territories, citing their low population density and alleged economic and cultural backwardness. Instead, they proposed representing them with appointed seats in the new upper house of parliament. Xinjiang was a hybrid between a province that was expected, at least formally, to conform to the same standards as other provinces, and a border region that was not considered equal to inland provinces. Because Xinjiang was officially a province, it had, in theory, a provincial assembly, although this did not hold elections and no elected delegates were sent to the Political Consultative Council in Beijing. At the same time, it was also represented within the framework of "border constitutionalism" by two appointed nobles sitting in the embryonic upper house. These differentiated policies essentially sought to parliamentarize the Qing patrimonial model, which granted privileges to the frontier nobility in exchange for their loyalty. However, these compromises left all parties dissatisfied.

The challenges posed by the proclamation of the Republic of China, in particular the declarations of independence by Mongolia and Tibet, led to increased insistence on the unity of the new state and the rapid adoption of the nation-state model. In the new "Republic of the Five Ethnic Groups"(wuzu gonghe 五族共和), Tibet and the Mongolian regions enjoyed representation in both the upper and lower houses. However, by analyzing the writings of early Republican constitutional lawyers and debates within the nascent Republican Senate, I show that this choice was not unanimously supported. Moreover, various modifications and exceptions inserted into the electoral law ensured that electoral participation was not strictly territorial, but once again fell under a differentiated system of frontier representation.