How do homogeneous cells spontaneously organize themselves into a complex embryonic structure ? Considerable progress in molecular and genetic biology has enabled us to identify the many players involved in this process called embryogenesis, but at the cost of fragmented levels of analysis. Today, researchers are seeking to overcome the traditional boundaries between disciplines by applying the laws of physics to the early stages of life. This approach opens up unprecedented prospects for treating infertility or tissue regeneration. But it also raises important ethical questions about our future ability to shape the living.

Interview with Hervé Turlier*, physicist at the Collège de France.

For Hervé Turlier, defining an embryo is no easy task. " I'm not sure I've ever tried to define what an embryo is ", he admits. His definition remains simple : " There may be a generic definition which consists of considering the embryo as an assembly of developing cells. " Fundamentally dynamic rather than static, this definition emphasizes two essential dimensions : time and space. Embryogenesis cannot be dissociated from morphogenesis, which refers to the progressive spatial organization of cells. According to the researcher, the embryo can be thought of as " a spatialization map ", in which cell layers and differentiations gradually emerge. This viewpoint shifts attention from molecular determinants alone to the overall structure of the embryonic system, conceived as a spatial entity in transformation.

This perspective ties in with the earliest approaches to developmental biology. At the end of the XIXth century, direct observation of marine embryos led researchers to question the spontaneous breaking of symmetries and the emergence of body axes. Hervé Turlier recalls that this research was driven by a fundamentally physical intuition of living processes, an intuition that contemporary molecular biology sometimes tends to relegate to the background. For the physicist, genes are not the most relevant level of explanation for identifying universal developmental mechanisms. While certain genes are conserved, developmental genes are mobilized differently according to species, context and time. This variability limits their explanatory scope when it comes to formulating general laws of morphogenesis.

This is why Hervé Turlier's research focuses on what he calls the " geometrical, topological and mechanical substrate " of the embryo, which he considers to be profoundly conserved in the course of evolution. In early embryogenesis, cells divide according to analogous mechanical mechanisms, regardless of the species involved. This constancy makes it possible to build generic models capable of capturing the fundamental principles of cellular self-organization. Genetics then intervenes as a secondary level, which the researcher compares to a " printed circuit " encoding the decision-making rules of cells, but not their basic architecture.

This vision changes our understanding of development. Physical forces become the true architects of the embryo. Genes merely adjust these universal processes, which it is now possible to model.

The tools of the new biology

At the heart of Hervé Turlier's research lies digital modeling, conceived as a form of experimentation. " Digital simulations are a bit like experiments ", he asserts, " provided we recognize that they remain pale copies of reality ". Their value lies not in an exhaustive reproduction of the living world, but in their ability to isolate minimal mechanisms and systematically explore their parameters. This approach is based on a preliminary mathematical process, fed by experimental data and exchanges with biologists. Once the mathematical equations have been established, simulations are used to test hypotheses, produce predictions and, above all, guide experimentation. For the physicist, the advantage is enormous. " We'll vary them to explore parameters in a way that's impossible to do experimentally. " Indeed, the computer can test a thousand scenarios in just a few hours. Hervé Turlier thus advocates a circular model of knowledge, in which theory and experiment feed off each other, as has long been the case in physics.

One of the most recent developments in this approach is the use of machine learning methods, not as an end in themselves, but as tools for accelerating inverse problems. These methods enable parameters or even model structures to be inferred automatically from massive data, paving the way for more predictive modeling of embryogenesis. " It will be possible to have a library of models. The objective will be to find the best model adapted to the data. " This technological revolution is speeding up research. It allows " to accelerate data analysis, to implement inverse problems in a very simple way ". Researchers are concentrating on the big questions rather than the calculations. This synergy between modeling and experimentation is revolutionizing biological research and opening up exciting prospects for healthcare.

Tomorrow's challenges

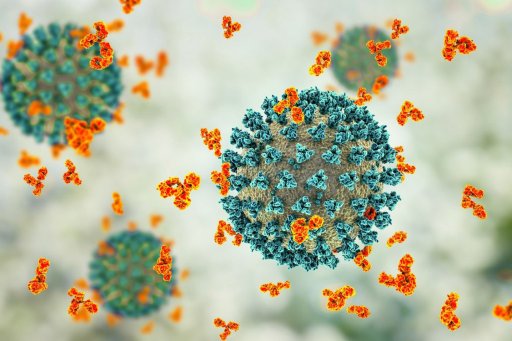

Hervé Turlier's work is not limited to theoretical ambitions. One major application concerns in vitrofertilization (IVF), within the French legal and medical framework. The aim is to identify geometric and mechanical markers of embryonic development that will enable us to better assess the implantation potential of embryos, beyond the essentially visual or empirical criteria that have prevailed until now. " Our originality lies in our in-depth understanding of the mechanisms at play ", he adds. This expertise enables us to predict embryonic viability with greater precision. Infertile couples could benefit from improved success rates. This application demonstrates the immediate medical utility of basic research.

In the longer term, understanding the mechanisms of cellular self-organization appears decisive for regenerative medicine and the development of organoids. " The idea is to take stem cells, put them in a box, then have them develop a new tissue. " This revolutionary prospect could transform medicine. " Imagine growing a liver to replace a failing organ, or regenerating nerve tissue to treat paralysis. The possibilities seem endless ! " This mastery of cellular self-organization opens up a new chapter in medicine. It promises treatments for diseases that are currently incurable.

However, Hervé Turlier also highlights the ethical and political issues associated with an increasingly predictive and manipulable biology. " The more we understand and control biology, the more we will be able to modulate and, potentially, hijack it. " For him, " the power to control embryonic development through synthetic biology opens up a horizon that is both magnificent and terrifying ". This ambivalence calls for collective reflection. How far can we modify living organisms ? Who decides the limits ? These questions go beyond science to touch on ethics and society. The scientific community must anticipate these debates. Supervision of these technologies is crucial to their responsible development.

The biophysical approach advocated by Hervé Turlier proposes a major shift in the way we think about embryogenesis : from gene to form, from molecular detail to global organization. It reconciles physics and biology in a unified vision of the living world. By rehabilitating modelling as a central tool for understanding the living world, it contributes to rebuilding the epistemological framework of developmental biology and reinforcing its dialogue with physics and mathematics. Far from opposing theory and experiment, this approach shows that it is in their rigorous articulation that a truly scientific understanding of the living world can emerge.

*Hervé Turlier is head of the Multi-scale Physics of Morphogenesis team at the Collège de France's Interdisciplinary Biology Research Center.