A specialist in soft matter and fluid mechanics, Lydéric Bocquet studies nanofluidics and its special properties, with a view to finding practical applications for the energy transition.

He has been invited to join the Technological Innovation Liliane Bettencourt Annual Chairfor 2022-2023 .

Nanofluidics is the study of fluid behavior in nanoscale channels. How did you become interested in this transdisciplinary science?

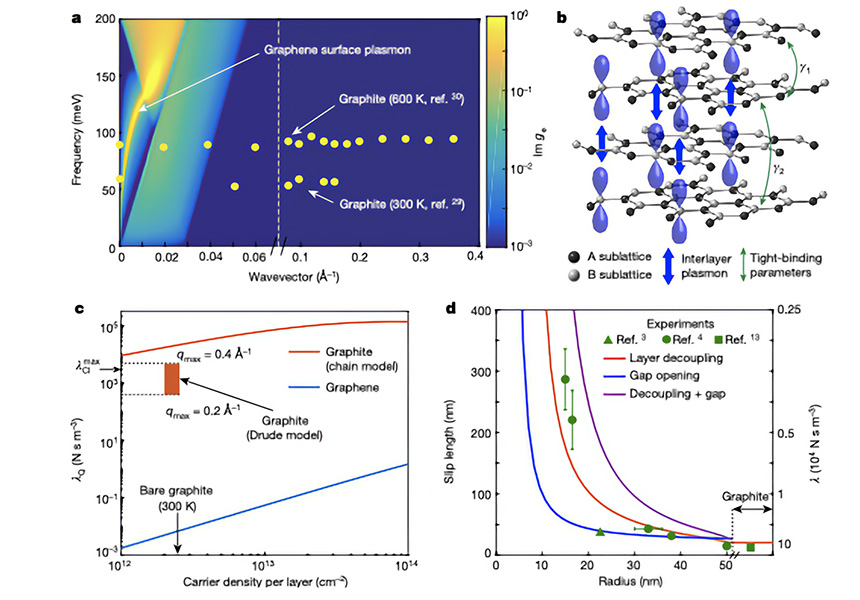

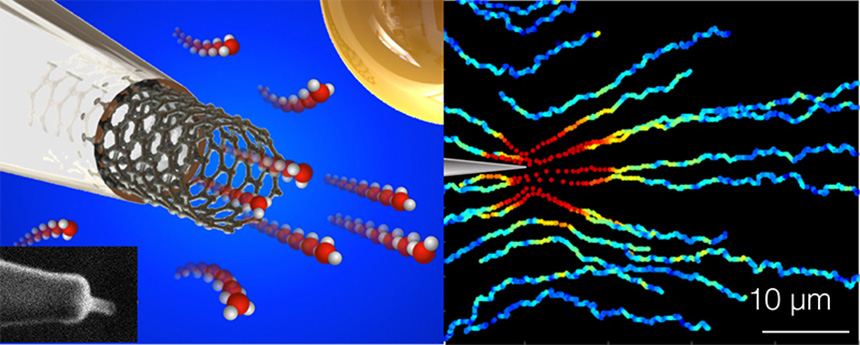

Lydéric Bocquet: I was originally trained as a theoretician. I studied statistical physics, i.e. physical systems made up of a large number of particles. Quite early in my career, I became interested in confined fluids and their particular properties, rather from a theoretical angle. But I realized that the question of fluids on very small scales was singularly lacking in well-controlled experimental studies. Many phenomena can be predicted theoretically, but without the means to apprehend nature's reality (which is often far more unexpected than we could have hoped), it's all a bit pointless. The major stumbling block was that we didn't know how to build nanosystems suitable for studying fluid transport at nano-scales, let alone quantify the molecular flows within them. In 2002, when I became a professor at Lyon 1 University, I decided to make a switch in my research by developing my own experimental activity. I set up a group with a few colleagues to work on so-called "soft matter", and then turned to the field of fluid transport in very small systems. With my team, I began exploring fluid flow in nanosystems, such as nanotubes, or more recently graphene[1] ; all these systems have opened up the field of possibilities for tackling these questions. Previously, the few results in this field had focused on membranes, and many of them had been very surprising or even controversial, for example with regard to the properties of nanotube membranes for water transport. Between 2008 and 2010, together with a few colleagues and some courageous students, we set out to investigate this problem by studying flows in single nanotubes. That was the beginning of the adventure, and since then I've been plotting my course around what's known as "nanofluidics" - the general study of fluid properties at nanoscales. I've tried to understand emergent properties that differ from what is usually known at large scales, which has made it a disciplinary field in its own right, at the interface between the continuums of hydrodynamics and the molecular, even quantum, nature of condensed matter. We work at the frontiers of the unknown, and some of our discoveries are frankly unexpected.

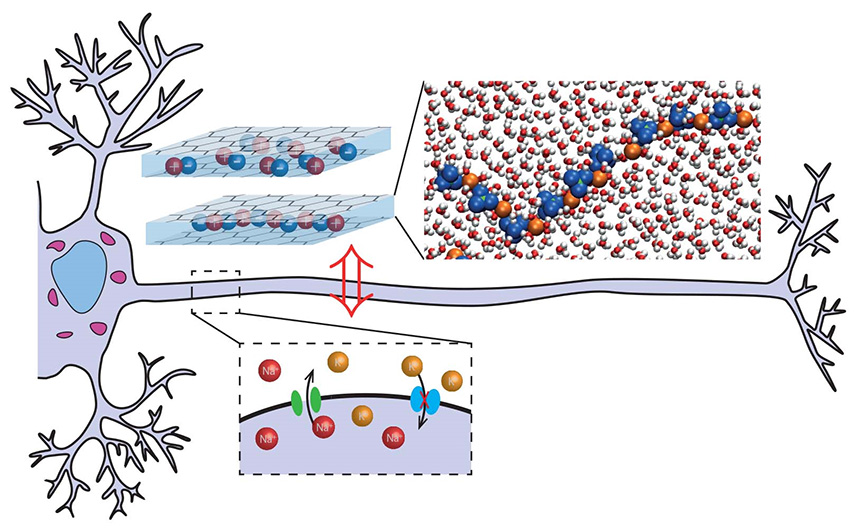

You recently worked on a so-called "ion neuron". What is this?

Typically, this is an unexpected application of nanofluidics. It began with a theoretical study of the properties of ionic systems in two-dimensional systems. We have recently been able to fabricate such channels using so-called "van der Waals assemblies", developed by the team of Nobel Prize winner Andre Geim, with whom we collaborate extensively. These assemblies are very interesting, as they enable us to fabricate extremely fine channels. So, for the first time, we were able to realize and perfectly control fluid or ion flows through channels measuring just a few angstroms[2], i.e. almost in two dimensions. In general, the properties of two-dimensional systems are very strange; ions interact very strongly, for example. Assemblies of ions were predicted to agglomerate to form a spaghetti-like structure. Through theory and numerical simulations, we have seen that these spaghetti can be broken, but then reassembled. It's a very complex dynamic. However, as these ultra-confined ion filaments are of considerable size, this phenomenon takes time to take place; and we see the appearance of a memory phenomenon. It's a functionality that evokes, even mimics, that of the neurons in our brain. We first demonstrated this theoretically in 2021, by reproducing some very basic neuronal functions. Then, in 2022, we moved from theory to experiment, and demonstrated these mimicked neuronal functions in our two-dimensional channels. In particular, with these nanofluidic channels, we reproduced in a very similar way the functions of the synapses which, in our brain, are the basis of learning. This is a perfect example of a completely unexpected result: we confine water on a nanometric scale and observe behaviors that have nothing to do with what we know on a larger scale.